The Anne Frank Dilemma

Due to letters, we have found a way to preserve people and their lives. Millions of letters were sent between families during WWII, and over time collections of them have been formed, both personal and private, that have an ornate effect on people. They expand both people’s knowledge of what it was like to be in the war, sparking a historical interest. Ones in museums and online collections have further shaped opinions on the war, allowing people to feel connected with the past. There is no question about the vitality of the letters, but when reading such personal letters feels unethical, why does one continue?

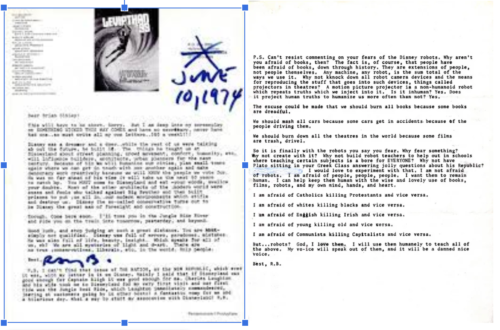

The Dear Bessie letters raise the question of ethicality because although Chris and Bessie’s story is adorable, their extremely personal letters are on display for the entire world. The author of the Dear Bessie Intro even said that “they wrote with far more passion then the could ever express in person.” These are real people whose children decided to share their personal stories with the world, an intrusive story that involves Chris constantly referring to Bessie’s chest. In an article by Irena Barker: Steamy Secrets of my Grandperents’ Private Letters, she explains her initial guilt for publishing the letters. Chris told Bessie the romance should be “our affair,” and he burned many letters to hide their contents. Yet questions of ethicality are pushed aside because these letters advance our “historical knowledge” and ability to connect with the past. The letters don’t tell us information about the battles and notable parts of war, but they do give us a way to connect to people that seem distant to us. There is an abundance of ethos and pathos when it comes to war letters (particularly those from soldiers). Letters from soldiers already have an added layer of pathos because you know the author worked hard to defend the country. Since the audience of these letters is loved ones that need reassurance, ethos is delivered in bulk.

What’s missing is the logos. The facts that would give these letters actual historical relevance, such as battle dates, location movements, and harsh conditions, are never included because of censorship laws, this recurring need to assure people of your safety, and, in Bessie’s case, the security of your relationship. So why read these letters? If they have no “historical significance,” why have so many people read these letters Chris sent to Bessie that one could argue is invasive? It’s because of the human need to sympathize. Chris and Bessie’s story is an excellent example of people using letters to feel more connected to the past. It’s hard to imagine what people went through at home and on the battlefront, but relatable letters help people put themselves in others’ shoes. Not many people have been on the front lines of a battlefield, but almost everyone can relate to the idea of missing a loved one. Some soldiers even tell stories of hanging out with friends and shopping. These letters may not provide crucial historical evidence, but they prove that people back then were just like people today. Once someone sympathizes with history, they can understand it. Since those who don’t learn from history are doomed to repeat it, sympathizing is the perfect way to remind oneself of the importance of history.

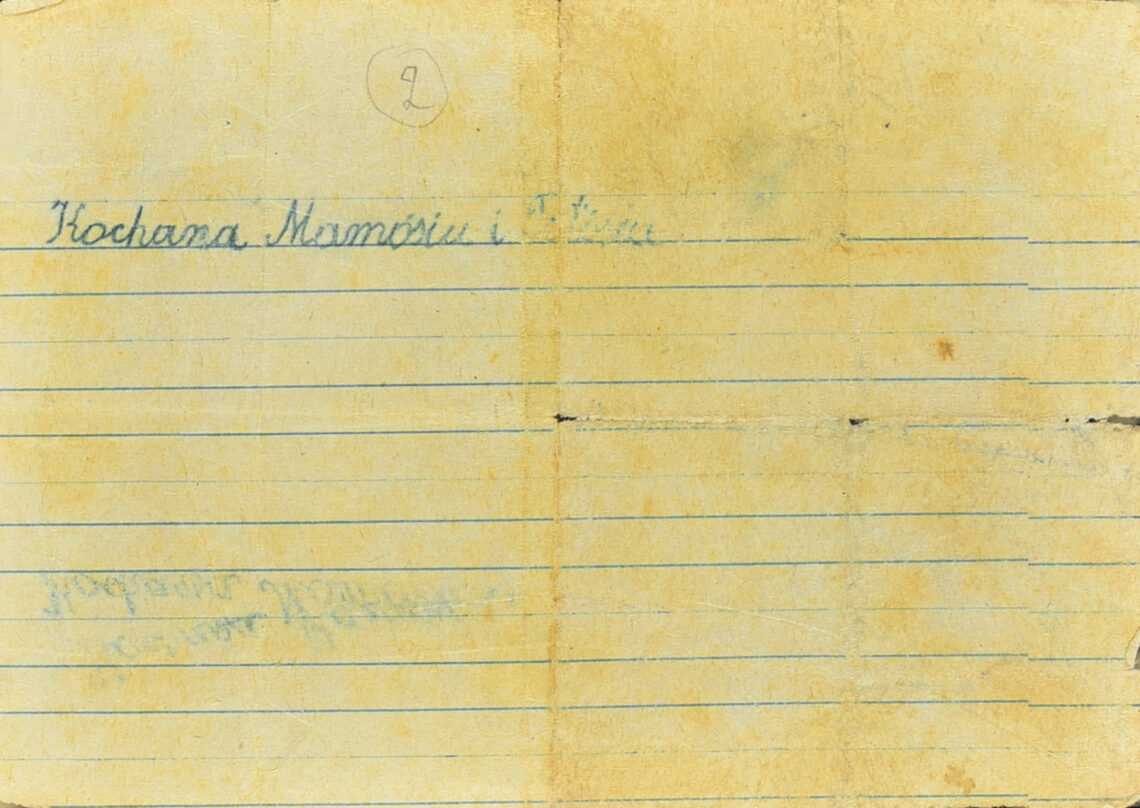

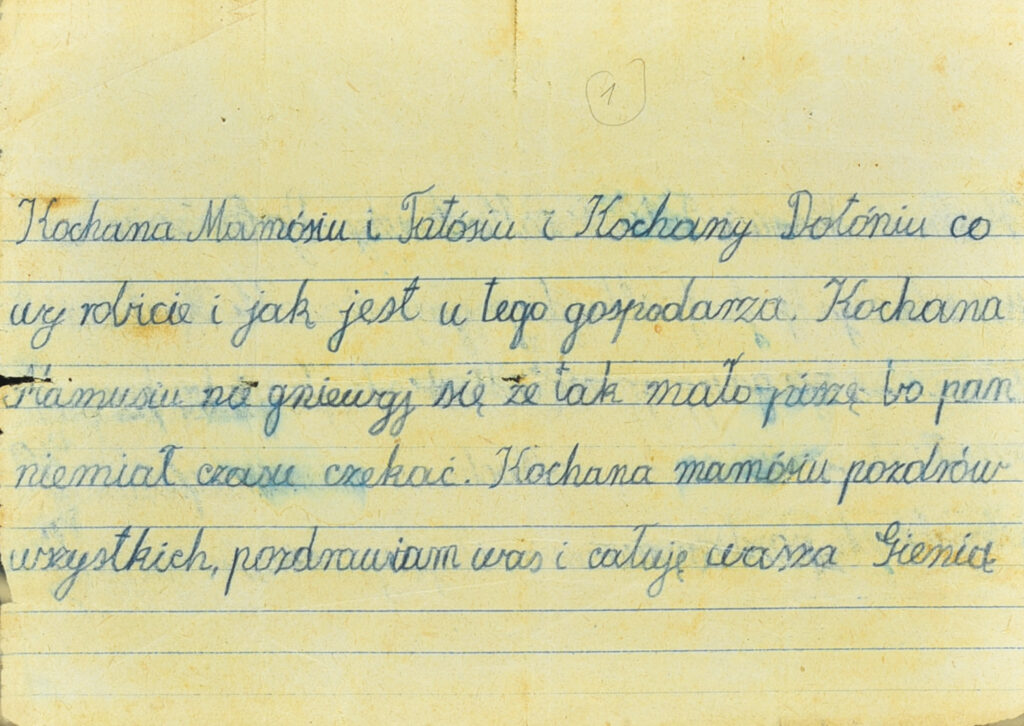

Another excellent example of ethicality vs. importance of history comes from a letter in the Yad Vashem Last Letters from the Holocaust exhibit. The last letter reads as follows:

“Dearest Mother and Father, and dearest Dulu [David]

How are you, and how is it at that man’s house?

Mother, don’t be upset that I’m writing so little

The man didn’t have time to wait.

Mother dear, please give my regards to everyone,

I wish you [well], and send kisses to you all.

Yours, Genya [Regina]”

Rivka-Regina wrote this devastating letter shortly before being killed. This letter, her final letter, her only letter, is her legacy. She’s upset at the letter and its lack of content; she wanted to say so much more, and I would have loved to have been allowed to read that letter, but it does not exist. Her parents gave testimony back in 1955. However, the letter was donated to the exhibit in 2015 by her brother (Moshe) for “external posterity.” Mosche understood that the letter would help future generations to understand the Holocaust better because they could sympathize with a sweet little girl whose final wishes were that she could have written more to her parents. However, it is easy to see that Rivak wasn’t pleased with the letter. Would she have wanted this to be how she is remembered despite its benefits in helping people sympathize with history? The idea of not being able to say everything you want because there isn’t enough time is a reality anyone can relate to. People can not only sympathize with Rivak, but they can emphasize with her. However, what can’t be forgotten is history. Rivka was placed with a Polish family to help her chance of survival. It was with this family she was murdered because a neighbor reported her. Distrust in people is another factor people can relate to because history has repeated itself, and once again, people don’t trust their fellow neighbors. Rivka’s letters remind people how awful the Holocaust was and that it can’t happen again. Is that more important than her wanting to write more?

There is no answer to whether the writer’s privacy is more important than the value of the letter to the public, and that is The Anne Frank Dilemma. Anne Frank’s Diary (which is written in letter format) is a universally known item that allows people to better sympathize with history. The Diary shows up in classrooms all over the world because it gives school children someone their age with similar values to sympathize with. It is a great way to introduce the Holocaust to young children so they can learn its importance. However, it is a diary. By definition, a diary is private and, most of the time, not meant to be shared with others, so there is a question as to whether the diary should have been published, especially since Anne starts each entry with “Dear Diary.” Although both the letters and Anne Frank’s Diary were initially meant to be private, people should be grateful for the overall availability to the public because countries that tend to rely on oral history don’t have the same access to knowledge that is provided by the eurocentric idea of letters and written history. Therefore people should continue to consume the knowledge they have available to them. However, one can’t forget that these are real people in real situations, and if the historical context is ignored, their privacy is being invaded for no reason and unfairly.